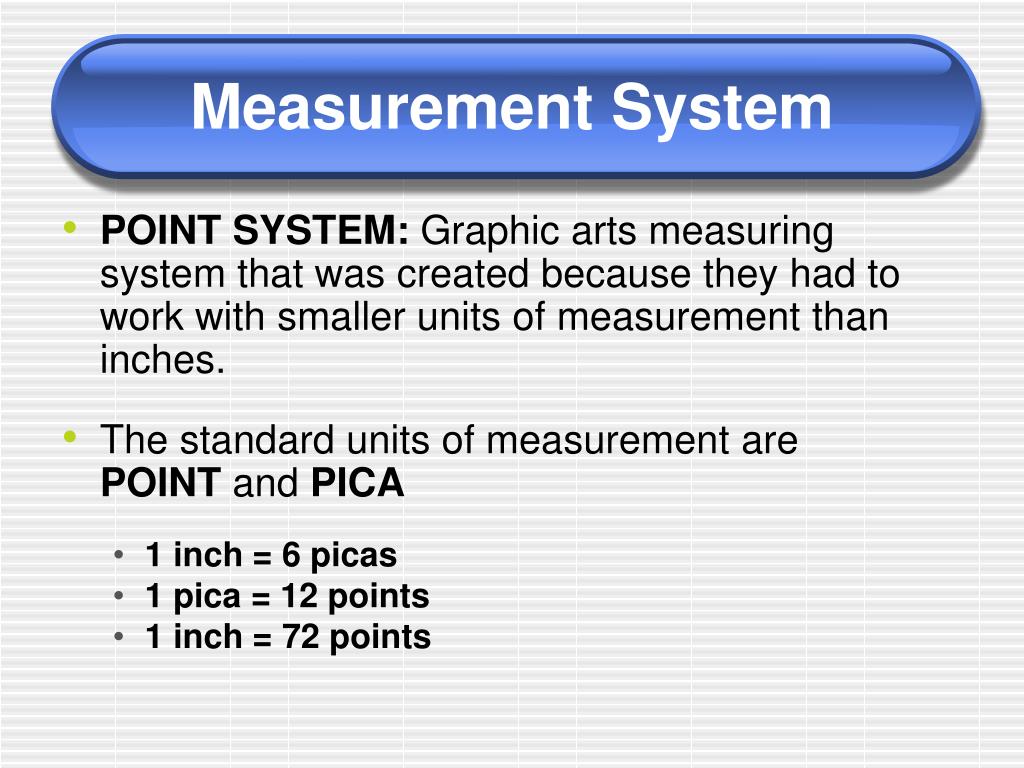

There was the “small pica,” approximately the same size as the “cicero,” equal to about 11 points, and the “double small pica,” about 22 points. Among the smallest was “diamond.” Other type sizers were called “pearl,” “agate,” “nonpareil,” “minion,” “cicero,” etc., without a lot of rhyme or reason, and the names varied by country. Instead, groups of type had names, which indicated their relative sizes (and sometimes font). Though its etymology is unclear, “pica” has been a typographical term since at least the mid-16th century, the Oxford English Dictionary says, representing a specific size of type, about, er, 12 “points.”īack then, individual foundries made their own pieces of type, and there was not much numerical standardization. The width of printed columns, by contrast, is measured in something called “picas.” Conveniently, 12 “points” equal one “pica” 6 picas equal 1 inch.īut it was not always the case. In the days before computer publishing, headline orders were often given as something like “2-36-2 Bodoni,” two columns wide, 36-point Bodoni type, two lines. You need to know, for example, that the size of the type is measured in “points.” Ordinary body type might be something like 10 “points,” with headlines starting around 12 “points.” In this measurement, 72 points equals an inch. on a Composition Machine, OR 24 Pt.People who work for newspapers often have to be familiar with a different measurement system than inches and feet. If possible key into the *Web* under the heading, >Leading and Slugsslip< but having access to Monotype,s extensive alignment charts, we just cast up, in 12 Pt. Harrild, Thank You for the acknowledgement of my humble offerings above, the object was to (hopefully) corroborate Your post(s) and to give the New devotees a little more to look into and learn. If you only use the first value, your measurements won’t work and you will pick the wrong spacing material and wonder what is going on. If you only use the second value, you end up having different cases with apparently the same font, but they are actually not the same.

The double notation (like 9/10, 72/60) really helps to avoid confusion. So I would label these fonts: 48p, 60p, 72/60p. But if you measure the body, the two larger sizes might both have a 60p body, because this significantly reduces the size and weight of the 72p letters! If you print them, you clearly see that they all have a different visual size. Let’s say you have 3 display sizes of one typeface: 48p, 60p, 72p. Not sure about the standard practice around the world, but I would label this font “9 on 10” or 9/10 for short.

But if you also had the original 8 point and the 10 point, you would see while printing, that the 9 point design is right between the 8 point and the 10 point in visual size. If you only had that single font without the original packaging, you probably wouldn’t be able to tell this and label it a 10 point font. A 9 point design for example might not be put on a 9 point body, but instead be cast on a 10 point body. This is sometimes used for uncommon or “in-between” type sizes. So in general, one can just measure the body and that’s the type size.īut there are also exceptions and this can easily cause confusion. In both cases, type size by default refers to the body, which still exists with digital type. Not with letterpress fonts, nor with digital fonts. While ascender line and descender line are part of a font’s “metrics”, type size is NOT generally defined this way. I would like to add some further clarifications:

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)